Chinese officials have characterized the 1989 demonstrations as “political turmoil,” and have charged participants with “counterrevolutionary activity.” And all reference to the massacre has been erased from public discourse, as well as from the Internet, to this day.

At first stunned with sorrow, Ding gradually came across other families who were also privately mourning this tragedy that their own national leaders were refusing to acknowledge. So, together with Zhang Xianling, a mother who had lost a 19-year old son, she founded the Tiananmen Mothers, a support group that has turned into a formidable voice for justice in China.

Ding’s grief found international expression in 1991 when she gave an interview to the U.S. news outlet ABC News in the United States. In that interview, the quiet philosophy professor from Beijing People’s University and member of the ruling Chinese Communist Party was remarkably forceful in her demands: an independent investigation of the massacre, compensation for victims’ families, and punishment for those found to be responsible

But these demands have not been met, and harassment has intensified over the years for Ding and her husband, a university professor in aesthetics, as well as for other members of the group. Ding and her husband were first hindered in small and insidious way in their work—for example, not being allowed access to new research students.

Ding was forced to retire early. She was then expelled from the Communist Party, and her husband was also forced to retire. They have been detained, followed, sent out of town during international events, disparaged to their friends, and kept under 24-hour police watch.

But none of this has deterred Ding in her pursuit of justice.

“Not only can they not suppress us, but in trying to do so they actually give us more strength,” she told CNN during an interview in 1999.

Ding Zilin, the co-founder of Tiananmen Mothers, center and her husband Jiang Jielian, at left, place offerings to commemorate the death anniversary of her son at the spot where he died during the 1989 crack down on pro-democracy protesters in Beijing in 2010. A plainclothes security officer films in the background as other police officers kept journalists and the public away. Ng Han Guan | AP

In 1994, Ding published a book, In Search of the Victims of June Fourth, about her quest to learn the circumstances in which people had lost their lives. Published in Hong Kong, the book is based on first-hand investigations and personal interviews of the victims’ families, and has been the only account of its kind until now

Her book earned the Vasyl Stus “Freedom-to-Write” Award in 2007.

In her book, Ding Zilin brings to life the faces of the many Chinese citizens who fell under the guns of their own country’s army. One was a 24-year-old graduate student who begged soldiers not to fire on civilians, and who was shot at short range with a pistol. Another was a man who kept coming back to the hospital door, carrying wounded on a plank, until he was brought in on a plank himself.

Another was a young medical student who was tending to the wounded, who lifted her head at the wrong moment and was instantly struck by a bullet that killed her. Others were young people trying to avoid the mayhem by running away.

All were shot.

“These are only the tip of the iceberg,” Ding told CNN.

“From these countless, bloody facts, I have reached this conclusion: The 1989 student movement and people’s movement were patriotic movements concerned with democracy and fighting corruption. They were not, as the government has said, counter-revolutionary rebels,” she said.

“”...I am willing to face any kind of danger, because there is no bigger punishment for a mother than losing a son.”

Over the last 25 years, the Tiananmen Mothers have repeatedly called for a dialogue with Chinese officials on a reappraisal of the crackdown. They have regularly petitioned the National People’s Congress and individual leaders. “We just write a letter, put a stamp on it, and mail it,” she said.

Ding retired from leadership of the group in 2014. Yet even now, at 78, she is considered a threat by China’s leaders.

“Social stability does not rely on bullets, on power and influence, or on deliberately forgetting the past,” she said to CNN, referring to present-day challenges to China. In her view, lack of accountability for the events of June 4, 1989 continues to fuel grievances among citizens in many other areas such as corruption and the unfair distribution of economic prosperity

“They are a hugely influential group, politically speaking,” said Sichuan-based rights activist Huang Qi of the Tiananmen Mothers in 2012.

As the date of the massacre’s 25th anniversary approached, extra care was taken to get the group’s members out of Beijing and away from the places where they could have commemorated their lost children.

“Such a great, mighty, and ‘correct’ party is afraid of a little old lady,” Zhang Xianling, the group’s cofounder, told NPR’s Louisa Lim in May 2014.

Ding is now getting older, and the other members of the group are also getting on in age. They may not live to see their demands met, but they remain an inspiration whose voices refuse to die.

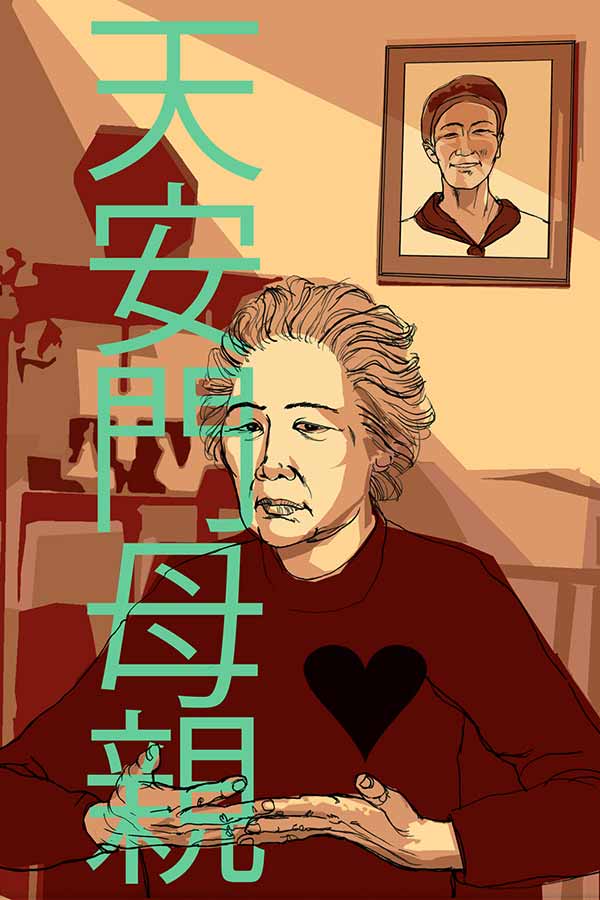

“It's Not OK: Women struggling for human rights” is a series of portraits of Asian women caught in the struggle for human rights in their communities. It was produced by Radio Free Asia. Download the

“It's Not OK: Women struggling for human rights” is a series of portraits of Asian women caught in the struggle for human rights in their communities. It was produced by Radio Free Asia. Download the