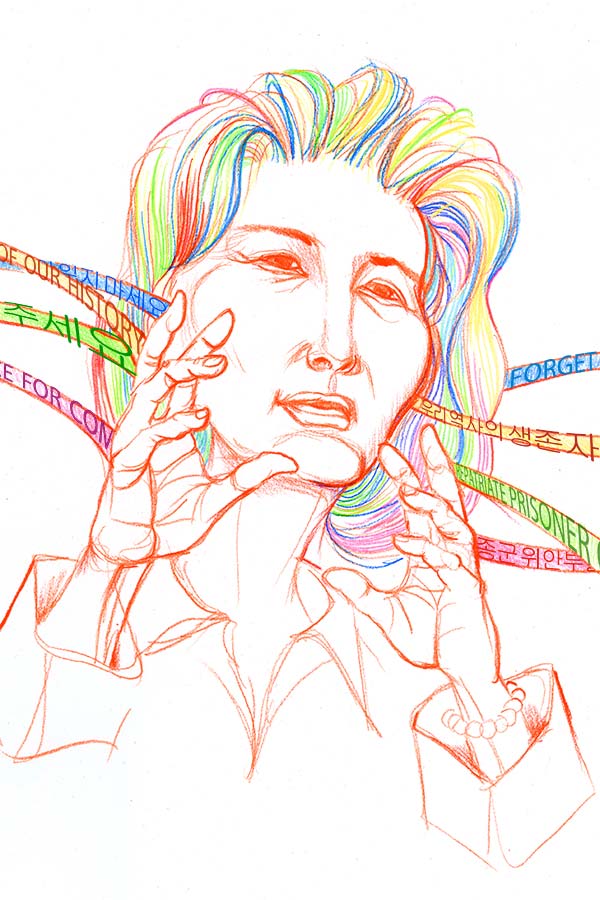

She also speaks up for the so-called “comfort women,” Korean women and girls who were forced into prostitution by the Japanese military during World War II. With an indignant “What kind of country is this?” she tries—and often succeeds—to shame South Korea’s political class into paying attention.

Park was a journalist for 12 years, and then a politician.

She was a member of parliament from 2008 to 2012 for the minority Liberty Forward Party, and a constitutional law professor since 1978. She still teaches law at Dongguk University in Seoul.

Park is also the founder of Mulmangcho, meaning “Forget-me-not,” an organization dedicated to helping North Korean defectors, especially the young and the old. Mulmangcho has built a school in Yeoju, Gyeonggi province, that caters to the needs of orphans and traumatized children. Mulmangcho also builds nursing homes for the elderly.

Discussing an 84-year old former POW and defector she knows who picks through trash to make ends meet, she angrily shouts, “What kind of country is this?” “My temper has gotten a lot worse since I took this job,” she admits.

During a visit to the United States in 2012, Park made an emotional appeal: “Meeting with North Korean defectors, I spent the last four years raging in anger and wailing to God, not comprehending how suffering like theirs can happen in human history.”

Park Sun-Young, following her 11-day hunger strike, attends a protest denouncing Beijing's repatriation of North Korean refugees outside the Chinese embassy in Seoul on March 9, 2012. Photo by Jung Yeon-Je | AFP

As her four-year term in parliament was coming to an end in 2012, she led a 77-day protest against the repatriation of North Korean defectors then detained in China, holding rallies in front of the Chinese Embassy in Seoul.

She even launched a 10-day hunger strike in an appeal to the U.N. Human Rights Council until her frail body collapsed. “I wanted to show that I was hurting too,” she explained to the Korea Herald at the time.

China has an extradition treaty with North Korea and regularly repatriates North Koreans who cross the border in the hope of reaching South Korea. Human rights activists say their fate on being returned is almost always imprisonment, torture, and death. Park has called these repatriations tantamount to murder.

On March 23, 2012 the United Nations Human Rights Council finally adopted a resolution condemning human rights violations in North Korea. The resolution passed by consensus when North Korea’s allies in the Council did not object. “It was a miracle,” said Park.

Although even her own family includes defectors from the North, she insists that it is her 30 years of professional experience that have kept her focused on the fate of “abandoned and forgotten” Koreans.

“I began taking care of North Korean defectors not because of personal relations, but because of my scholarly conscience and professional ethics,” she told an RFA reporter in 2012.

She has traveled 13 times to Japan to negotiate recognition and compensation for the World War II “comfort women,” victims of sexual exploitation by the Japanese army. Successive Japanese governments have alternatively acknowledged and then denied such mistreatment. The issue remains unresolved.

“I began taking care of North Korean defectors not because of personal relations, but because of my scholarly conscience and professional ethics.”

As a lawyer, Park knows her facts. “Article 3 of the Constitution defines nationality,” she said. The article reads: “The territory of the Republic of Korea consists of the Korean Peninsula and its adjacent islands. By extension, the South Korean government has the duty to protect the human rights of North Koreans, just as it does the rights of South Koreans.”

As a politician and journalist, she is well aware of the media’s importance when fighting for a cause. In one noteworthy effort to shed light on the plight of defectors in South Korea, she organized a foot-washing ceremony three days before Easter 2012.

“Many people said that they could not take off their socks, though, because they had lost their toes to frostbite during their escape,” she recounted. “But I convinced them, saying that this was not their fault but rather a part of our painful history. I told them, ‘Let’s just gather our courage and express this pain.’” The defectors then exposed their mutilated feet to the public.

Park remains obstinate in the face of others’ complacency. Holding a bundle of letters written by former South Korean POWs now living in the North, she announced that she was founding her own publishing company to make them public. None of the South Korean companies she had contacted had wanted to risk publishing them.

In March 2013, the United Nations adopted a Human Rights Council Resolution establishing a commission to investigate “grave violations of human rights” in North Korea. The commission began its work in December 2014, but the issue of POWs is not on their list of concerns.

Park's job is far from over.

“It's Not OK: Women struggling for human rights” is a series of portraits of Asian women caught in the struggle for human rights in their communities. It was produced by Radio Free Asia. Download the

“It's Not OK: Women struggling for human rights” is a series of portraits of Asian women caught in the struggle for human rights in their communities. It was produced by Radio Free Asia. Download the