But she was suddenly released in 2009—“Pick up your stuff and go outside” is the summary order she recalls—and went on to found the Yangon School of Political Science with friends and colleagues to “train political activists.”

She then co-founded the Rainfall Gender Studies Group to promote women’s participation in democracy building and took part in study groups on Asian values and democracy.

Their motto: “We will think what others dare not think.”

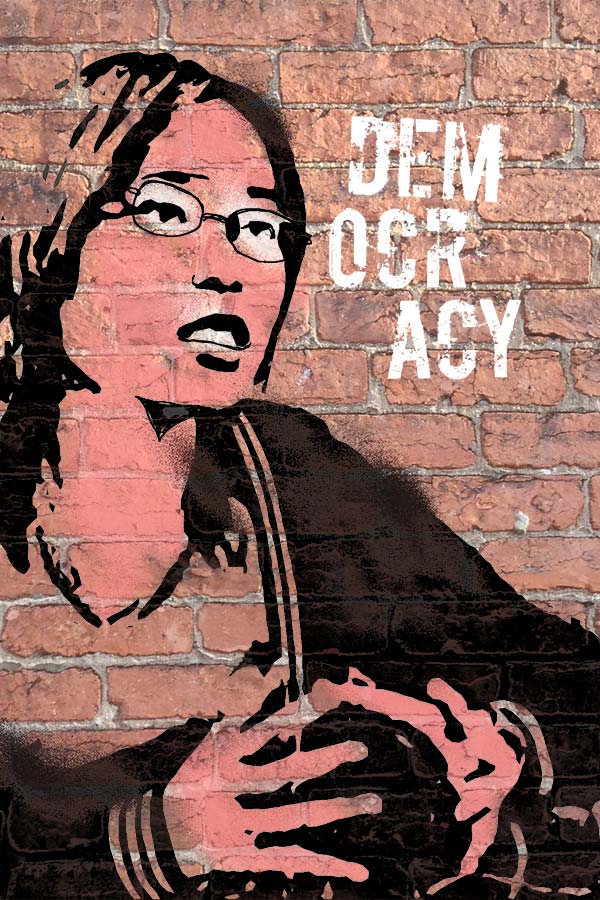

In 2012, Zin Mar Aung was one of 46 women to be honored with the U.S. State Department’s International Women of Courage Award.

Of her years spent in solitary confinement, she recalls: “I did not feel lonely, because I had made up my mind,” demonstrating a steely resolve to devote her life to the advent of a civil society in her country with a role for women at its heart.

Her prison sentence included seven years for each offense, one of them being the public reading of a poem promoting political freedom.

“We saw no rule of law. We were sentenced as they liked, and then some were released, just as they liked,” she recalled later. This understanding gave her the strength to endure. “My conscience was clear,” she said in an interview with Radio Free Asia in 2012.

Zin Mar Aung also credits the inspiring role presented by NLD leader and Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, who spent 15 years under house arrest before being released in 2010.

“[Burmese] people do not prefer a woman to be a leader,” said Zin Mar Aung, underscoring the cultural ground remaining to be covered for women like herself, who do not benefit from the historical connections associated with Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of Burmese independence hero General Aung San.

Burmese pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi and Zin Mar Aung, a former political prisoner, attend a BBC World Debate during the World Economic Forum on East Asia in Naypyitaw in 2013. Photo by Soe Zeya Tun | Reuters

“Listening to her speeches and her political discourse is really inspiring. It encouraged us to get involved in politics,” she said.

Myanmar’s military seized power twice after the country gained independence from Britain in 1948, first in a 1962 coup d’état, and then a second time in 1988.

The opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) won elections to a constitutional assembly in 1990, but the junta refused to recognize the results. And as students organized and built a force of political resistance, Zin Mar Aung was arrested alongside many other activists. Some are still in jail.

In 2010, NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi was released and Myanmar held elections for the country’s parliament. In 2012, the NLD won 43 of the 46 seats contested in by-elections.

Although Zin Mar Aung recognizes that voices like hers have now gained a measure of freedom, she does not trust the sincerity of Myanmar’s former military rulers, arguing in an August 2013 interview that the apparent liberalization of Myanmar has been aimed only at allowing foreign investments and loans to flow into the country to counterbalance economic domination by China.

“The very first period of prison life is the most terrible ... But if we can overcome this period, we feel free – we feel stronger.”

And though she has welcomed early moves to professionalize Myanmar’s military and police, more recently she has sounded alarms over attacks on the country’s Muslim Rohingya minority and over an apparent rollback of promised press freedoms.

She also opposes laws proposed by a radical Buddhist movement that would require Buddhist women to obtain permission before marrying outside their religion. “As a Buddhist, it makes me very sad to see this,” she said in an August 2013 interview.

Now, she has become even more forceful in voicing her concerns for Myanmar, and has recently received death threats. “Liberalization is over,” she told The New York Times in July 2014.

“It's Not OK: Women struggling for human rights” is a series of portraits of Asian women caught in the struggle for human rights in their communities. It was produced by Radio Free Asia. Download the

“It's Not OK: Women struggling for human rights” is a series of portraits of Asian women caught in the struggle for human rights in their communities. It was produced by Radio Free Asia. Download the