But more than 50 years of military rule and ethnic conflicts have destroyed these freedoms. Many Myanmar women—particularly members of ethnic minorities—have had to endure not only discrimination but also rape, fear, and the breakdown of their families and communities under atrocious circumstances.

In the country’s new climate of transition to democracy since 2011, women continue to contribute to every part of the economic fabric. They plant and harvest rice, drive heavy equipment on construction sites, maneuver buses in city traffic, and manage shops and restaurants.

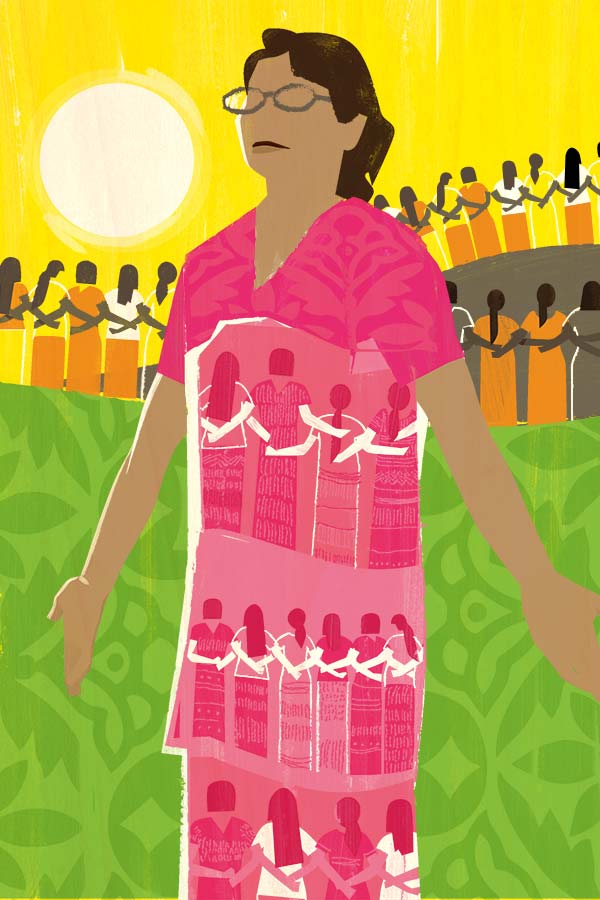

Susanna Hla Hla Soe

However, according to the United Nations Development Fund (UNDP), only 18 percent of females over the age of 25 had a secondary education in 2010.

“The main challenge for women today is the cultural and traditional belief that women are supposed to stay home. They are marginalized,” explains Hla Hla Soe who is quick to point out that only 4 percent of members of parliament are female.

“You can count on your fingers how many women have been chosen as village heads,” she told Radio Free Asia (RFA) in December 2014.

“We aim to have 30 percent of MPs be women. We need to work harder to reach that goal,” she told RFA soon after running in the Yangon Municipal elections in December 2014—an election she lost to Khin Maung Tint, a man, because of “irregularities,” she said.

She is filing a complaint with the election commission.

Hla Hla Soe is a force to contend with, and she is being noted internationally for her dedication to alleviating poverty and bringing women’s voice to the table—whether in peace negotiations, drafting new laws, or combating human trafficking.

“She was paying attention to those issues when no one else was,” says Khin Maung Nyane, deputy director of RFA’s Myanmar service.

Born in Insein, in the northern suburbs of Myanmar’s former capital Yangon where ethnic Karens have often settled, she was brought up with deep Christian values of charity. Her parents hosted foster children from the remote areas of Karen State to give them an education, and what was then a family tradition became a calling for her.

She earned a bachelor’s degree and a master’s in Zoology at Yangon University while volunteering for World Vision, a Christian humanitarian NGO dedicated to fighting global poverty.

Starting as a clerk, she became project manager and then rose rapidly through the ranks to top positions. World Vision also sponsored her education with leadership workshops and an MBA in NGO leadership from Eastern University, a Christian university in Philadelphia, in the United States.

In 2003, she joined the newly founded Karen Women’s Action Group (KWAG) to empower women in war-torn Karen State. “We were just working with our bare hands, without any funding or assistance. We used money from our own pockets,” she told the magazine Irrawaddy in 2013.

When Cyclone Nargis ripped through the Irrawaddy Delta in 2008, Myanmar’s then-ruling military junta refused offers of international assistance and forbade NGOs access to the disaster area.

Undeterred, Hla Hla Soe led an emergency relief team to resettle families and rebuild their homes. “It was hard to build trust,” she confessed to Irrawaddy four years later. “We were also afraid to speak to the media,” she said.

During these same years, she came to learn of the human trafficking of local girls to neighboring countries, and she worked with her own government and that of China to follow the traffickers and bring the girls home.

She later founded a group dedicated to combating the trafficking of women and girls, though she recognizes today that “the problem has gotten worse.”

In 2010, she became KWAG’s executive director, and in 2012 she earned a humanitarian award from InterAction, a U.S. NGO dedicated to disaster relief, for her “extraordinary leadership.”

A wife and the mother of a teenage daughter, Hla Hla Soe has become a consummate advocate for women.

When President Obama traveled to Myanmar in 2012, she was able to hand him a letter, which read: “We do not have proper legal protection of women in our country. Today in Myanmar, a woman can be sold, forced into prostitution, and physically and mentally abused by family members.”

“We don’t want our family members losing their lives because of war. We want our children to be educated. We want to live happily with our children.”

Now she campaigns not only for a fair share for women in the administration of the country, but also for their place at the peace negotiation table. “We ethnic people have suffered from armed conflicts,” she emphasized in her letter to Obama.

“We are happy about the peace process, but it needs to be transparent and inclusive,” she wrote.

Unbridled development is also a risk for Myanmar’s ethnic groups, and Hla Hla Soe has clear views about this as well: “If someone asks, do you need electricity, we will answer yes,” she said at a peace rally in Yangon in June 2014. “But not if our rivers fill with red sand.”

In her work with other women’s groups in Myanmar, she chairs the Women’s Organizations Network of Myanmar (WON), an umbrella group of local organizations. She is also a steering committee member of Women’s Protection Technical Working Group, a network that includes United Nations agencies and other international NGOs working for the protection of women. And she is president of the Women’s Peace Network, a local group of women activists headquartered in Yangon.

Above all, Hla Hla Soe’s quest is for peace in her country, which has such a painful history.

“We are women, we are mothers, we are sisters,” she said in Yangon while wearing a sky-blue shirt, a symbol of her call for peace.

“We don't want our family members losing their lives because of war. We want our children to be educated. We want to live happily with our children.”

“It's Not OK: Women struggling for human rights” is a series of portraits of Asian women caught in the struggle for human rights in their communities. It was produced by Radio Free Asia. Download the

“It's Not OK: Women struggling for human rights” is a series of portraits of Asian women caught in the struggle for human rights in their communities. It was produced by Radio Free Asia. Download the