The family’s hometown of Kardze is now a part of China’s Sichuan Province. And the ancient monastery, destroyed and then rebuilt, today shelters about 700 monks—less than half the religious community it once housed.

These events colored the rest of Rinchen Khandro’s life.

In a 2013 interview with Tricycle magazine, she recounts how her illiterate mother one day announced: “We’ll sell my jewelry and give the children an education. That’s something nobody can take away.”

So Rinchen Khandro went on to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree at Loreto College in Darjeeling, India, and later married Tendzin Choegyal, a younger brother of Tibet’s exiled spiritual leader the Dalai Lama.

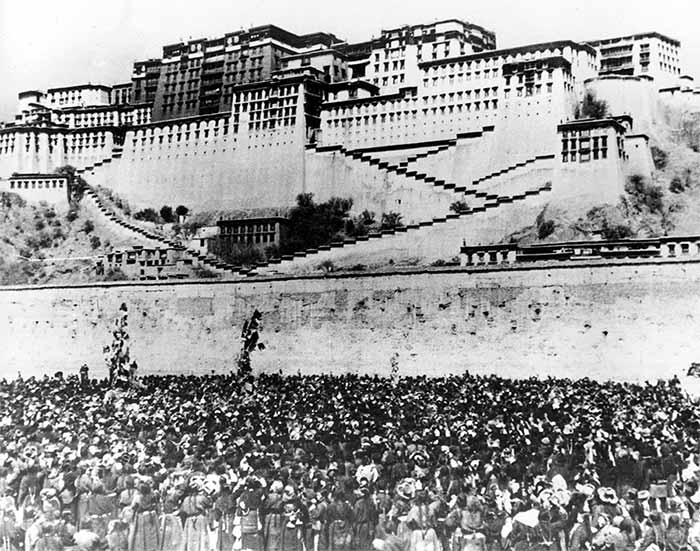

Thousands of Tibetan women silently surround the Potala Palace, the main residence of the Dalai Lama, to protest Chinese rule and repression, Lhasa, March 17, 1959. AP

Nurturing Tibetan culture and Buddhist values and teachings in her life, Rinchen Khandro has become over the years one of the most gracious yet forceful representatives of Tibet in exile, always insisting that exile is temporary and that Tibetans—wherever they live—are a community in which women have a role to play.

Referring to Tibetan hopes for an eventual return to their homeland, “we will never give up, and our [future] generations will carry it on,” she declared during an interview with a visiting Canadian journalist in 2007.

Regarding the network of Tibetan schools created by the Tibetan government in exile, she told Tricycle magazine: “[These] schools have given the Tibetans in exile their language, a sense of belonging, and a sense of identity.”

After marrying and settling in Dharamsala, India, where the Dalai Lama also lives, Rinchen Khandro was a traditional stay-at-home Tibetan woman, raising two children and taking care of her mother-in-law until her death.

But once those years were over, she thought: “Now I need to do something for the community.”

In 1984, she became one of the founding members and the first president of the Tibetan Women’s Association (TWA), a body dedicated to the empowerment of Tibetan women. The association is responsible for the training of Tibetan women as leaders in their communities all over the world.

The TWA later came to global attention in September 1995 when it staged a demonstration during the U.N.’s Fourth World Conference on Women, held in Beijing.

There, in the heart of the ruling Chinese Communist Party’s seat of power, nine brave Tibetan women marched with silk scarves tied over their mouths as symbols of repression, with tears streaming down their faces. The scarves themselves were a gift from the conference’s Chinese hosts.

Tibetans attend a protest march organised by Tibetan Women's Association to mark the 50th anniversary of the failed Tibetan uprising against the Chinese rule in 1959, in the northern Indian hill town of Dharamsala in 2009. Abhishek Madhukar | Reuters

In 1987, the TWA founded The Tibetan Nuns Project to focus on the well-being of the many nuns who were arriving in India from Tibet as refugees, some of whom couldn’t even write their own names.

Then, in 1994, Rinchen Khandro was elected to the cabinet of the Tibetan government in exile, where she worked to improve the situation of Tibetan refugees and raise international awareness of the Tibetan cause. Her combination of Western education and deep attachment to Buddhist values made her the perfect representative to speak in international forums.

“The voices of Tibetan people, which speak for peace everywhere, must not only be heard, but listened to,” she told the Canadian reporter. “Buddhism teaches [one] to live happily.”

She later also served as the Tibetan exile government’s Minister of Education and left a strong impression on visiting American students.

“She said, don’t cling onto things when they don’t turn out how you hoped they would. She said, let go and start fresh. It was a great interview to have at the very end of our trip,” one of those students wrote on the travel blog of the Watsonville, CA, Mount Madonna School.

Rinchen Khandro Choegyal’s tireless service was later recognized in 1997 by a U.S. State Department Women of Courage Award.

But her work was still not over.

“The voices of Tibetan people, which speak for peace everywhere, must not only be heard, but listened to.”

Over the last 27 years and still today, she dedicates her efforts to the Tibetan Nuns Project.

An institution born out of necessity when nuns fled Tibet in large numbers in the 80s, the project has blossomed into a major not-for-profit organization providing shelter and educational opportunities—previously available only to men—for five nunneries in North and South India.

Tibetan nuns traditionally were never as numerous as monks, and never had the same access to higher learning. Under Chinese rule, however, they endured an equal share of suffering.

“When the nuns arrived in India, they were ill, exhausted, traumatized, and impoverished. Many nuns had endured immense physical and emotional pain,” recalls venerable Lobsang Dechen, a nun herself and co-director of the Tibetan Nuns Project.

Today, under the careful watch of Rinchen Khandro, the project provides education, food, shelter, and health care to 700 Tibetan nuns from all Tibetan schools of Buddhism and ranging in age from pre-teen to mid-80s.

In 2013, 27 nuns sat for the first time for the Geshema degree, a doctoral degree in Buddhist studies. Their studies included all the academic challenges presented to Buddhist monks, including traditional debates about the nature of “truth.”

Following their graduation, exiled Tibetan spiritual leader the Dalai Lama urged the successful degree candidates to take up active roles as teachers. “Until now you have relied on monks to teach you, but in the future it will be very important that there are also nuns to teach nuns,” he said.

“It's Not OK: Women struggling for human rights” is a series of portraits of Asian women caught in the struggle for human rights in their communities. It was produced by Radio Free Asia. Download the

“It's Not OK: Women struggling for human rights” is a series of portraits of Asian women caught in the struggle for human rights in their communities. It was produced by Radio Free Asia. Download the